It was the first week of December, 1835. Outside San Antonio, the Texian volunteers, having marched from Gonzales, were about to pack it up and head home. The thinking was General Cos and his army were too strong and too firmly entrenched to be pried out of the city.

Ben Milam had a different idea. Old Ben had made his home in Texas since 1818, having first come here to trade with the Comanches. Any man who decided to do that was not easily scared or discouraged.

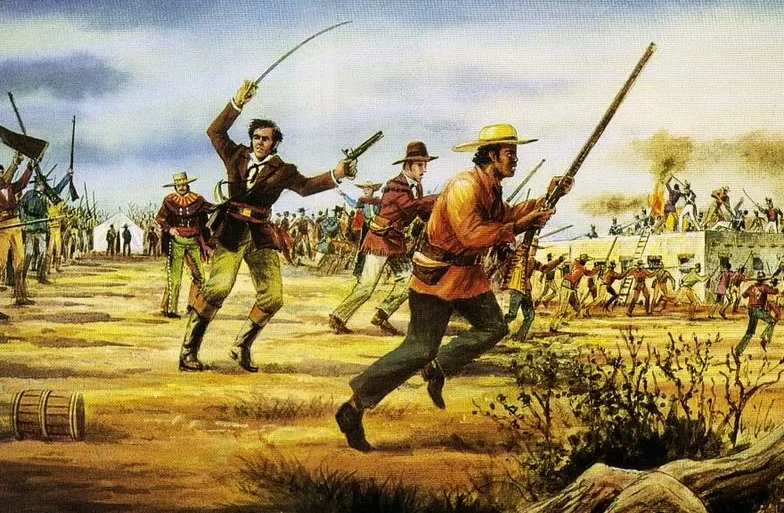

Disgusted with the situation, he emerged from Edward Burleson’s tent and yelled angrily, “Who will go with Old Ben Milam into San Antonio? Who will follow Old Ben Milam into Bexar?”

About 300 volunteers said they would follow him.

And so they did.

In 1870, Dr. George Cupples related the events of that week to the Alamo Literary Society as follows:

Early on the morning of the 5th of December, 1835, Col. Ben Milam attacked the city; Samuel A. Maverick as guide, with Milam at the head of the right division, moving down Soledad street to the LaGarza House.Johnson, commanding the left, marched down Acequia street to the same point, with Deaf Smith for guide. The cannon posted at the corner of the Main Plaza swept these streets.

To procure water, our troops took the Veramendi House by digging a trench of five feet in depth across the street during the night of the 5th, and so going back and forth with heads bent to avoid the grapeshot.Of the seven hundred volunteers under Burleson at the “Old Mill’ above town, only two hundred fifty were under Milam. Others joined them two days later, but the greater number had gone home or to Goliad, where a force was then gathering to move against Matamoras.

On the 7th, Milam was killed in the yard of the Veramendi House, being shot through the head; and by his side stood Mr. Maverick.

On the 10th, the Mexicans ran up the white flag of surrender. The Texan troops had fought incessantly night and day, and had taken all the square block of buildings fronting the north side of the Main Plaza, by digging through the walls of the houses from one to another.

Where the Plaza House now stands there lived the priest, Padre Garza. From this house the Texans made a charge and took and spiked the guns, the fire of which had been concentrated on that building and was fast crumbling it down.

In this charge Col. Ward lost a leg, and the young Carolinian, Bonham, an eye. The Mexican gunners fled or were cut to pieces. This was on the morning of the 10th, and was followed by the capitulation of Gen. Cos, who was permitted to retire with his troops across the Rio Grande.

That’s how San Antonio came into Texian hands and set the stage for the Siege and Battle of the Alamo.

The death of Ben Milam is a story familiar to most anyone who has strode the River Walk and seen the large cypress which still stands on the bend across the river from where the Veramendi House stood. It’s from that tree that the fatal shot was fired.

Creed Taylor was there and later recorded what he witnessed.

“Milam carried a small field glass (a present to him by General Austin). With this glass…Milam was viewing the Mexican stronghold on the plaza. At this moment a shot rang out and Milam fell, the ball piercing his head. I heard the shot and saw Milam fall and instantly turned to ascertain the direction from which the shot was fired.

One of those present in the yard called attention to the fact that at the report of the shot he saw a white puff of smoke arising from the branches of a large cypress tree that stood on the margin of the river. At this announcement all eyes were turned in the direction of that tree, the outline of a man was seen, several rifle shots rang out and the corpse of the daring sharpshooter crashed down through the branches and rolled into the river.

After the surrender, Colonel Sanchez told Col. Frank Johnson and Captain Bennet, in my presence, that this sharpshooter, Felix de la Garza, was the best shot in the Mexican army, a half-brother of Almonte, and that General Cos was deeply grieved over his death.”

Ben Milam was buried where he fell in the yard of the Veramendi House. In 1848 he was moved to the new City Cemetery, later renamed Milam Park in his honor.

James DeShields wrote:

“Though buried some ten years, the body, it is said, was unchanged, and the old warrior looked natural. The boots in which he was buried were sound and would have done to wear again. The black silk kerchief in which his head was tied looked perfectly new, except for the bloodspots”

The cemetery and park fell into disuse, and by the time the city got around to erecting a marble monument to Col. Milam, the site of his burial was only approximately known.

It was not located until 1993 during restoration of the park. Archaeological investigation found a burial just slightly north of where the monument had sat.

The skeletal remains were examined by anthropologists at the Smithsonian Institution. They wrote:

“The skeleton described in the preceding sections represents a robust, active, right-handed, white male who was about 5 feet 9 inches tall. He was 40-49 years of age at death. At the time of death, which resulted from perimortem trauma (a gunshot wound) to the head, he was suffering from osteoarthritis, which was most pronounced at the knee joints, and from extensive disc herniation in the lower spine. The latter condition, together with well-developed muscle attachment sites, indicates heavy labor or some other activity involving substantial biomechanical stress.”

Col. Milam was re-interred in the park that bears his name on the 11th day of December, 1994.

May he rest in peace.

Categories: Texas Exceptionalism, Texas Heroes, Texas Revolution