| The report that follows was written in 1819 by an unknown officer serving under Lt. Lawrence Kearny of the schooner USS Enterprise. The US government was fed up with Lafitte preying on American merchantmen, and Kearny had been sent to Galveston by the Navy to see that the pirate left the settlement he called Campeche. |

To the captain’s hail, “Is Commodore Lafitte in the harbor?” a tall, good-looking person in a palmetto hat, with bushy whiskers and mustaches, answered in good English, “Captain Lafitte is.”

“I wish to see him.”

“You’ll find him on board that brig yonder.”

We pulled to the brig – she was full of men. All sorts of faces, white, yellow, black, and dingy, reconnoitered us from the bulwarks, and seemed to look with little love at the cocked hat and epaulettes of the regular man-of-war

“Is Captain Lafitte on board?”

“No, señor,” a hardy-looking, gray-headed old fellow answered, taking his cigarette from his mouth and proceeding to light a fresh one. He gave us some directions in Spanish, which I did not under stand; the amount of which, however, was that “El Capitan” might be found on board the schooner. And to the schooner we accordingly rowed.

To our inquiry, Captain Lafitte answered himself, with an invitation to come on board.

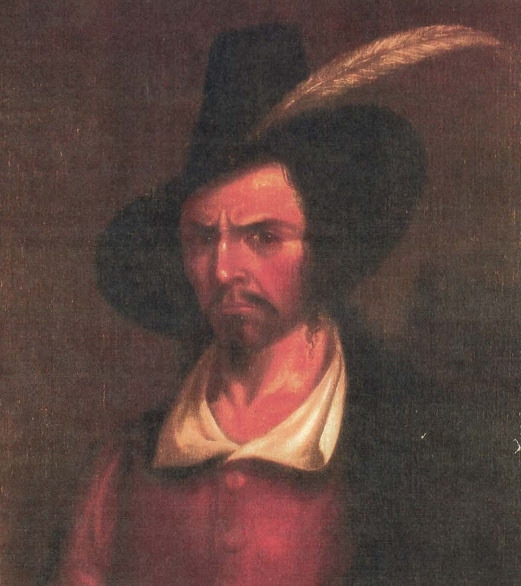

My description of this renowned chieftain, to correspond with the original, will shock the preconceived notions of many who have hitherto pictured him as the hero of a novel or a melodrama.

I am compelled by truth to introduce him as a stout, rather gentlemanly personage, some five feet ten inches in height, dressed very simply in a foraging cap and blue frock of a most villainous fit.

His complexion, like most creoles, was olive; his countenance full, mild, and rather impressive but for a small black eye which now and then, as he grew animated in conversation, would flash in a way which impressed me with a notion that “El Capitan” might be, when roused, a very ugly customer.

(collection of the Rosenberg Library)

His demeanor toward us was exceedingly courteous, and upon learning Captain Kearny’s mission, he invited us below, and tendered the hospitalities of the vessel.

“I am making my arrangements,” Lafitte observed, “to leave the bay. The ballast of the brig has been shifted. As soon as we can get her over the bar we sail.”

“We supposed that your flotilla was larger,” Captain Kearny remarked.

“I have men on shore,” said Lafitte – not apparently noticing the remark – “who are destroying the fort, and preparing some spars for the brig. Will you go on shore and look at what I am doing?”

We returned to the deck, and Lafitte pointed us to the preparations which had been made on board the brig for getting her to sea. The schooner on which we were, mounted a long gun amidships and six nine pounders a side. There were, I should think, fifteen or twenty men on deck, apparently of all nations; and below I could see there were a great many more.

There was no appearance of any uniform among them, nor, to the eyes of a man-of-war’s man, much discipline. The officers, or those who appeared such, were in plain clothes, and Lafitte himself was without any distinguishing mark of his rank.

On the shore we passed a long shed under which a party was at work, and around which junk, cordage, sails, and all sorts of heterogeneous matters were scattered in confusion. Beyond this we came across a four-gun fort. It had been advantageously located, and was a substantial looking affair, but now was nearly dismantled, and a gang was completing the work of destruction.

“You see, Captain, I am getting ready to leave. I am friendly to your country. Ah, they call me a pirate. But I am not a pirate. You see there?” said he, pointing suddenly toward the point of the beach.

“I see,” said our skipper, “what does that mean?”

The object to which our attention was thus directed was the dead body of a man dangling from a rude gibbet erected on the beach.

“That is my justice. That vaurien (good-for-nothing) plundered an American schooner. The captain complained to me of him, and he was found guilty and hung. Will you go on board my brig’”

On this vessel there was evidently a greater attention paid to discipline. Lafitte led the way into his cabin, where preparation had already been made for dinner, to partake of which we were invited. Sea air and exercise are proverbial persuaders of the appetite; and Mr. Lafitte’s display of good stew, dried fish, and wild turkey was more tempting than prize money.

Under the influence of the most generous and racy wines he became quite sociable. Lafitte was evidently educated and gifted with no common talent for conversation.

“I should like very much to hear your life, Captain,” I remarked.

He smiled and shrugged his shoulders. “It is nothing extraordinary,” he said. “I can tell it in a very few words. But there was a time” – and he drew a long breath -“when I could not tell it without cocking both pistols.”

“Eighteen years ago I was a merchant in San Domingo. My father before me was a merchant. I had become rich. I had married me a wife. I determined to go to Europe, and I wound up all my affairs in the West Indies. I sold my property there. I bought a ship and loaded her, besides which, I had on board a large amount of specie – all that I was worth, in short.

“Well, sir, when the vessel that I was on had been a week at sea we were overhauled by a Spanish man-of-war. The Spaniards captured us. They took everything – goods, specie, even my wife’s jewels. They set us on shore on a barren sand key, with just provisions enough to keep us alive a few days. An American schooner took us off, and landed us in New Orleans.

“I did not care what became of me. I was a beggar. My wife took the fever from exposure and hardship, and died in three days after my arrival. I met some daring fellows who were as poor as I was. We bought a schooner, and declared against Spain eternal war.”

“Fifteen years I have carried on a war against Spain. So long as I live I am at war with Spain, but no other nation. I am at peace with the world, except Spain. Although they call me a pirate, I am not guilty of attacking any vessel of the English or French. I showed you the place where my own people have been punished for plundering American property.”

Categories: Texas Biographies, Texas Heroes, Texas history