Have you ever wondered when and how Texians became Texans?

The Culturnomics team of the Institute for Quantitative Social Sciences at Harvard has helped answer the WHEN part of the question.

They “constructed a corpus of digitized texts containing about 4% of all books ever printed. Analysis of this corpus enables us to investigate cultural trends quantitatively…focusing on linguistic and cultural phenomena that were reflected in the English language between 1800 and 2000.”

The Culturnomics team has kindly made their research tool available to the public.

So I put it to use figuring out when Texians became Texans in the eyes of the world.

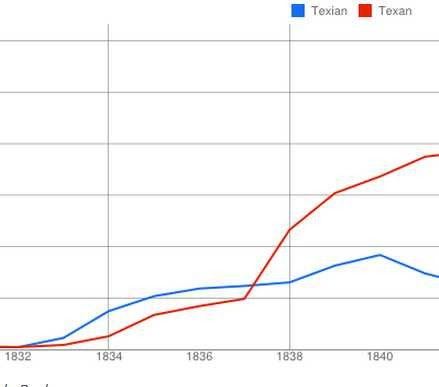

By 1838 Texan was being used at 2.5 times the rate of Texian. The fortunes of Texan steadily rose, and by 1850 it was being used twelve times as often.

So that’s when Texians became Texans in the eyes of the world, but what about in their own eyes?

For that answer we can thank the University of North Texas Libraries’ Digital Projects Unit. Those folks have digitized thousands of Texas newspapers (and much, much more).

Searching that archive we find that during the 1830s, Texian was being used in Texas at four times the rate of Texan.

During the 1840s it dropped to twice the rate.

Then in the 1850s the use of Texan in Texas newspapers exploded to more than twice the rate of Texian.

Drilling down deeper, it appears that Texian jumped the shark in Texas some time during 1846, just after annexation.

I don’t have an answer for the WHY part of the question.

The most logical idea is that new emigrants to Texas were accustomed to using Texan and there weren’t enough old-timers to keep correcting them all. The new term overwhelmed the old.

William Kennedy may also have had something to do with it. He included this footnote in his 1841 history of Texas:

“Texas and Texans are the correct English appellations of the land and its inhabitants; in Spanish, Tejas and Tejanos (pronounced Tehas and Tehanos). Texian, Texasian, Texican, and Texasite, all of which have been used to designate the people of Texas, are more or less corrupt.”

Texasian? Would be pronounced TexASian or TexASIAN?

Anyhow, Kennedy’s book was highly influential. So much so that an anonymous Texian felt it necessary to respond to that footnote, writing:

“It is an indubitable fact that the inhabitants of Texas, literate and illiterate, have almost universally adopted the term Texian to define their political individuality, and we are not apprised of any rule of language that is violated in doing so…

Texas ends in AS. We cannot on the instant, recollect any country or place whose name has the same termination. Paris ends in IS, and we say Parisian; Tunis has a like terminus, and we say Tunisian…

We, therefore, conclude there can be no imperative law of language adverse to the term Texian, which we have almost universally adopted, and which is fully incorporated into our public documents…

We fancy that Texian…has more of euphony, and is better adapted to the convenience of poets who shall hereafter celebrate our deeds in sonorous strains, than the harsh, abrupt, ungainly appellation, Texan – impossible in rhyme to anything but the merest doggerel.”

But it was too little and way too late.

Though written in 1842, the Texian response was not published until 1857, when it appeared in the Texas Almanac as a curiosity.

We were all Texans by then.

What Makes a Texan?

Michelle’s Answer:

We recently debuted our line of Texan/Tejano Generations shirts. In the days following the launch, we received messages from some puzzled Texans seeking guidance about where their Texas journey technically began.

“My g-g-grandfather came to Texas from Kentucky and settled in Ector County in 1889. My g-grandfather was the first generation born there. So what generation do I order?”

My answer: the best formula to figure out which Generation shirt to buy, at least to my eyes, lies not on your birth certificate but in your ethos.

A Tale of Two Texans

I know a gal who is a proud member of a Texas lineage society whose only claim to being Texan seems to be just that – her body contains the DNA of a man who served the Republic.

She takes no action to serve Texas in her own life or preserve our history, but she’s a member of a special club and will claim to be more Texan than you or me.

On the other hand, I met a gentleman last week who was born in Ohio but is the walking embodiment of a Texan…hungry for knowledge about our history, active in promoting the preservation of that history, raising his children with Texan values.

Are both of these folks Texans? You bet!

The incident of the Ohio man’s birth doesn’t make him any less than a true Texan. I would argue that if there’s a hierarchy of Texianity, he’s far more Texan.

Why? Because his actions emit the light of the Lone Star far more than that certificate on her wall does. He emulates the spirit of the men who built this place, while she just stands on their shoulders.

So here’s your formula – count back to your ancestor who first came to Texas, worked the land, helped build up a community, raised a family and became a part of the fabric of this place.

Doesn’t matter if they were born in Tennessee or Prussia. Whatever generation that ancestor is from you, that’s the shirt you buy.

If anyone wants to play dueling birth certificates with you, just tell em’ being Texan is a state of being, not a piece of paper. Stephen F. Austin wasn’t born here either.

Semper Texas!

Michelle Haas

Categories: Texas Culture, Texas history