| Michelle here, taking a break from habitually refreshing my COVID case data screen, to tell you a story that you may not have heard but are living out in real time. |

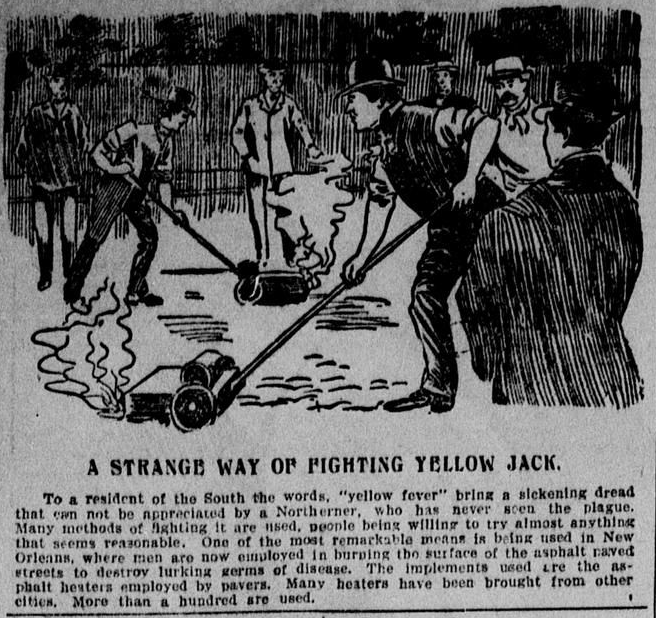

| When Texas was younger, her pioneers lived in fear of yellow fever, scarlet fever, malarial fever, dengue fever, a handful of generic bilious fevers, and about as many poxes. Before the first blue norther came in each year, people stayed on edge. It came with the pioneer territory. So it’s no surprise that in September 1897, when cases of yellow fever popped up at Ocean Springs, Mississippi, Texans tensed up. Those who had survived the epidemic 30 years before recalled the losses of entire families, and the deaths of thousands. But things were different in 1897. Telephones supplemented telegraphs, bringing the news faster, and with the inflection of the human voice. People also traveled more, faster and farther than they had in 1867. A fantastic web of rail connected Texans to Texas and to everywhere else. The good part about 1897 was that Texas found out about the outbreak in real time. The bad part about 1897 was that people from infected places might be arriving at the train station in your town any minute. What if they were bringing with them a bug that could wipe your community off the map? The fever moved down the coast. Mobile, Biloxi, Bay St. Louis. Port towns all over the U.S. quarantined against ships from Gulf ports. Texas likewise locked down her ports to ships from any point east of New Orleans. Police inspected inbound trains to make sure passengers weren’t coming from infected towns. The people were cautiously optimistic. Then news of 12 cases in New Orleans hit the papers, and all hell broke loose. New Orleans health officials swore that it was just some lesser fever, but nobody cared. Towns all along the coast declared absolute quarantines against New Orleans and other infected places. Cotton futures plummeted. Ripples of the news were felt in the great east coast financial kingdoms.  Texas papers daily carried the updated number of cases, deaths and recovered patients in New Orleans. To try to keep her commerce alive, New Orleans declared herself squeaky clean and announced new clean-up measures. It would now clean…wait for it…the asphalt! Just in case yellow fever germs were living on the blacktop, New Orleans was singeing the surface. But Texans didn’t care. Towns in East Texas outright refused to allow trains to stop at their stations. Keep it moving at 25 mph…or else. The State Health Officer, Dr. Swearingen, posted armed guards at all dirt roads entering Texas from Louisiana. Quarantine camps, like the one below, sprang up outside of railroad towns. Travelers who were shut out of their destinations because of quarantines, but couldn’t turn back because trains weren’t running east, were held at these camps for 2 weeks to prove they were disease-free.  Places like Marlin and Georgetown locked themselves down entirely. Nobody could enter. If you lived there and were returning home after lockdown was declared, well that was just too bad. Bryan sent a health official to inspect Houston, on behalf of its citizens, who had heard rumors that the Bayou City was infected. Denton also issued a quarantine against any outside entry. Big towns and little towns did the only thing they thought might save them – they cleaned. Galveston appropriated $5,000 to clean the city gutters, pull weeds and pick up trash. Houston declared that any structure within 250 feet of a sewer line had to tie into the line. Corpus engaged in a city-wide cleanup effort. In Milam County, a volunteer force in Cameron disinfected the town. As far as I know, nobody scorched the pavement to kill germs in Texas. By the third week of September 1897, the papers were filled with quarantine notices and rumors of “suspicious cases.” Caldwell, Navasota, Wills Point, Brenham, Tyler, Calvert, La Grange, Huntsville, Brookshire, Hearne, Columbus…even Dallas declared a quarantine against trains and humans from infected or suspicious places. The holdouts were few. Waxahachie, Palestine and Corsicana said they didn’t believe yellow fever was coming to Texas, so they remained open. Naturally, other towns quarantined against the open towns. Overall, everyone quarantined against each other in the spirit of self preservation. Then nothing happened. Texas thought it had dodged a bullet. The Houston Post published this triumphant but creepy victory cartoon to kick off October 1897.  Orange reported it was resuming business. Hillsboro and Waco lifted their quarantines. Public schools re-opened on October 4 in Richmond. A large crowd at Sabine Pass greeted the first train to arrive there in weeks. Merchants and markets rallied. Everyone was alive again. And that should have been the end of the story. ….but it wasn’t. An October 12, 1897 statement by Dr. Juan Guiteras of the U.S. Marine Hospital, published in the Houston Post, upended Texas in way that made the events of September look like dinner theater. Dr. G’s report declared that he had inspected Houston and Galveston, and the fever was present in both places. Yellow Jack, Bronze John, the Saffron Scourge – it had arrived in Texas! About 12 cases, he said, most of them recovered, but definitely yellow fever. Houston and Galveston doctors moved swiftly to denounce Guiteras’ statement, claiming it was just dengue fever, not yellow fever. City councils passed resolutions declaring that their cities had one malady and not the other. But the damage was done. Texans flew into action. Now Texas towns declared quarantines against Houston and Galveston, as well as other places down the coast. The old shotgun quarantine method went into effect. Try to enter from Houston and you had to deal with men with guns. The San Francisco Bulletin summed it up well:  The town of Bryan not only tried to prevent trains from stopping there, they barred trains from entering the county entirely. Picture it like a train robbery, but without the theft part. Brazos County was not alone in this tactic. Texas A&M entered total isolation and declared it would stay that way until the first frost. In Fayette County, a Muldoon company loading a huge order of rock bound for the Galveston jetties stopped work…no train would be sent to infected Galveston. Folks in Wharton and other towns just fled. Trying to avoid contact with other people – even their neighbors – they fled to the interior and North Texas. At Brenham, there was a run on groceries and supplies (yep….19th century toilet paper pirates). People living outside of town were preparing for “a siege in case this yellow fever business comes to the worst.” The news from La Grange two days after the cases were announced: “Our streets have been almost deserted this week, owing to people being afraid to come into town.” On the day the Associated Press broke the news of cases in Texas, the Western Union office at Houston was flooded with 750 telegrams and had to call in extra hands to deal with the 900 responses to be sent out. Houston immediately bought from Washington D.C. a new device for mechanical fumigation of mail. The machine, by way of a paddle with thin metal tines, slapped tiny holes in each envelope to allow sulphur or formaldehyde fumes inside to kill germs on the letters. San Antonio locked down, but the Austin city council couldn’t agree to quarantine or not to quarantine, so they just adjourned without doing anything at all. Mayor Rice of Houston, at the pleading of the Houston Cotton Exchange, issued an invitation for town representatives from the Texas interior to come to Houston and inspect it for themselves. He even offered to provide free transportation. Each town decided independently whether or not they wanted to risk sending their most trusted citizens into Houston. In the end, the handful that went were able to convince others that Houston wasn’t a hotbed of yellow fever. Texas Health Officer Swearingen released the state ordered quarantine of Houston and Galveston when no new cases had appeared for about 10 days. Less than 2 weeks after the panic began, it subsided. Houston theaters announced they’d resume plays. Public schools re-opened across the state. And the Houston Post trumpeted the news everyone was waiting to hear.  Trains will run again! Texans and commerce began to move. They shopped, sent letters, received newspapers, saw their neighbors. Texas was gonna be okay. Little did they know, it was those new-fangled window screens they’d installed since the last epidemic that had saved them from heartbreak and death. The discovery that mosquitoes were the cause of the dreaded disease was still a couple years away. Newspaper editors, with a few days’ hindsight under their belts, scoffed at the experts who had raised the alarm of the fever in Texas. Halletsville bragged on itself for knowing all along that the scare was no big deal. Ain’t hindsight grand? This thing we’re living through right now is like 1897 in many ways. Every day, we’re bombarded with figures and death tallies. Every day we’re reminded to stay at home. Every day we’re told that the economy is wrecked. There are pertinent things we don’t understand yet, just like those Texans didn’t know the damn mosquitoes were the cause of yellow fever. We’re leery of the various alarms & predictions of experts, but afraid nonetheless. We’re bringing back shotgun quarantine at the Louisiana border. But we are adapting and we are pioneering new ways of doing what needs to be done. We are doing as Texans have always done – moving ably through uncharted territory. And while we don’t yet know how our version of this story ends, we must remember this: the trains will run again. You can count on it. God & Texas, Michelle |

If you would like to read more about how our forebears did things, this is a good choice: Click Here to read all about it. |

Categories: Texas Culture, Texas history