by Michelle M. Haas

There aren’t many places on earth where Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna is viewed favorably. Can you think of any?

Mexico? Nope.

Texas? Definitely not.

USA? Nuh uh.

There’s no love for Santa Anna anywhere, really. None that you hear about. Though he held the Mexican presidency eleven different times between 1833 and 1855, his aggregate time in office was less than five years.

Santa Anna was capricious and opportunistic, not exactly known for his civic achievements or improving the lives of those who lived under his various reigns. And let’s not forget his affinity for having people killed with assembly-line efficiency.

So would you believe me if I told you there is a patch of God’s green earth where the architect of the butchery at the Alamo and Goliad (shout-out to Zacatecas, too!) is revered?

Before you start sending me hate mail, hear me out….

In the Bolivar province of Colombia is a city called Turbaco. In 1850, it was a quiet village of about 300 people just inland from the Caribbean, when Santa Anna – on a dictatorial sabbatical – arrived on the scene.

A couple of years into exile and denied access to his preferred Mexican haciendas, the cash-rich general sought to establish a nest in Colombia. He moved into an old home and turned it into a beautiful dwelling place at the center of town.

Then Santa Anna built a small kingdom around him.

(Semantic detour: As modern folks, many of us use the term “hacienda” to casually refer to home, as in “I’ll meet you back at the hacienda.” But a Mexican hacienda was more akin to what we know as a plantation. In the same way that a subsistence farm was not a plantation, a rancho was different from a hacienda. A hacienda was defined by its large land holdings producing commercial crops, with staff – usually forced labor of one kind or another – their dwellings, and a main house. Implements for getting finished goods to market – sugar mills, tobacco kilns etc. were also located on the grounds.)

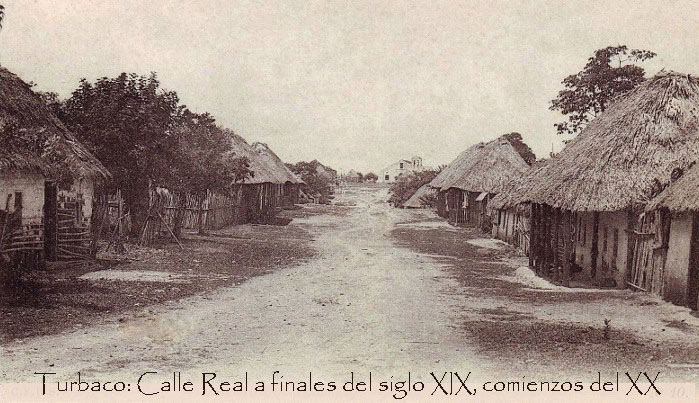

The Turbaco hacienda was called La Rosita, after a legitimate daughter of El Presidente. Though its owner was disgraced and deposed in Mexico for losing Texas in 1836, (then almost half the country in 1848) the main home at La Rosita was called, ironically, Casa de las Tejas – house of the tiles – for its clay tiled roof, which stood in stark contrast to the thatched-roofed miserable shacks of the village.

When Santa Anna took up residency in his new digs, he also set aside some of his land on high ground to establish a cemetery for the community. Claiming that he wished to live and die there, he even erected a mausoleum for himself.

He paid for improvements and embellishments to the parish church, and widened the Camino Real to Cartagena so that carriages could move goods freely to and from the port. He loaned money to the locals, or tabaqueros. Whether it was interest-free or the start of debt peonage relationships depends on who you ask.

Citizens of the town would come around to Casa de las Tejas to hear him tell war stories and solicit his advice. They didn’t care what he’d won or lost. They didn’t know anything about his brutal deeds in Texas. To them, he was just a career military man who’d been in a thousand battles in service to his country.

He was beloved by many, in a variety of ways apparently, siring a plethora of illegitimate kids, having them baptized with the surnames of close friends rather than his own. Some of that first generation are buried in the cemetery he founded and a bevy of present-day tabaqueros claim to be descended from love-children of the dictator, as well as of his legitimate son, Ángel. The locals say Santa Anna had a penchant for Creole women.

On his vast property holdings in Colombia, Santa Anna grew tobacco, produced sugar and raised cattle. The slave population of Bolivar was among the highest in Colombia, and chattel slavery remained legal there until a year into Generalissimo’s tenure, then shifted to peon servitude (also called debt slavery.) So Santa Anna most likely employed a mix of forced labor to run his operations. Between La Rosita and the properties he owned in Cartagena, it is said that thousands of souls – paid and unpaid –worked his land for him.

The income from this fiefdom allowed him to live the plush life to which he’d become accustomed in Mexico. La Rosita, of course, had a cock-pit where he could indulge his fancy for bird betting. And breeding fine horses was a must. These two traditions continue among tabaqueros to this day.

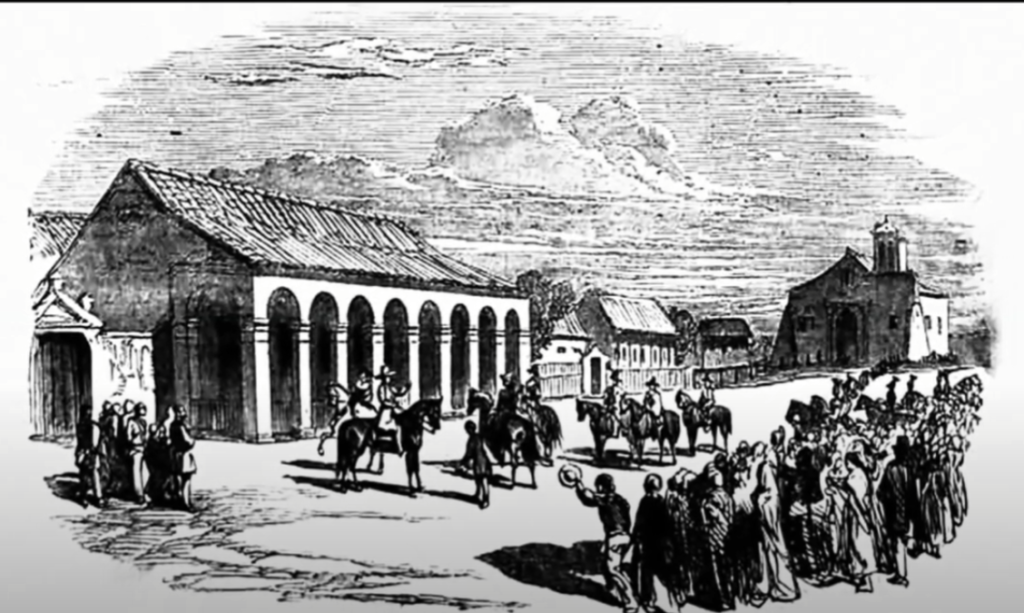

Santa Anna was in residence at La Rosita as part of his post-Mexican War exile from 1850-53. He put on his dictator hat again in 1853, only to slink back to La Rosita under threat of revolution in 1855. In his memoirs, he claims he was greeted by the citizenry who joined in the town square to raise their voices in welcoming song. That might be hubris, but it might well be true.

Back in Colombia, he licked his wounds, bet on the cockfights and enjoyed the good life until he saw the political saloon doors of Mexico swinging his way yet again. In 1858, he left Turbaco for the last time, informing the residents of the area that his country was being scandalized by anarchy and required his services. Only the most dire need of his country could tear him away from the people of Turbaco, he said.

Papers in the U.S. bet that this was Santa Anna’s final reunion tour in Mexico. As one Ohio Paper put it:

Whoever may be able to govern Mexico, it is tolerably certain that this broken-down hero never can. But for his remarkable facility & felicity in escaping all mortal danger, we should expect from this last attempt a highly tragic end. As it is, we look for comedy only – or simply broad farce.

Their bets were correct. Santa Anna would not return to power and would die blind and broke in the 1870s, after wandering around in exile for years.

The mayor and other dignitaries of Turbaco, though, were much aggrieved at his departure. In an 1858 farewell letter signed by 90 prominent citizens of the area, they called him a father and benefactor of Turbaco, and told him that he embodied “everything great, everything beautiful, everything sublime and everything heroic” that could exist on the face of the Earth.

After Santa Anna departed that last time in pursuit of power, he sold off parts of his hacienda, leaving the Colombian town with the infrastructure to become agriculturally powerful. Roads, sugar mills, good livestock for breeding and cultivated lands did a lot for their small town economy.

Today, the place is a thriving city of more than 100,000 people. About 100 of those believe they’re descended from Santa Anna and they keep in touch, acting as a sort of lineage society. And they are always seeking out new relatives. These people are proud to be descended from him regardless of his villain status in Mexico or Texas because of what he did for their town.

While the vast acres of La Rosita have long since been developed, Casa de las Tejas still stands, and today serves as the mayor’s office. The main drag through town is called the Avenida de Mexico, in honor of Santa Anna’s birthplace. Along with the coat of arms, the national anthem and other patriotic basics, school children learn about the Mexican general who developed their town. One of the most widely repeated myths passed on to the tabaquero kiddos is that Santa Anna built a tunnel under Casa de las Tejas, leading to the nearby Santa Catalina church. This was his escape hatch in case the Mexican government ever came looking for him.

In 2020, the leaders of the city began a project to erect statues of the most prominent men in Turbaco. Santa Anna is among the four men to be memorialized. They say they want to “rescue [their] history” from being lost. That should sound familiar to many of us. There are no statues of Santa Anna in Mexico

It’s trendy right now in certain circles to say that the Alamo Defenders weren’t heroes because some had owned slaves or that Travis abandoned his wife (he didn’t) or so & so committed such & such crime before coming to Texas…and it’s chic to argue that certain statues should be erased.

I always respond to those people: “Whatever their deeds outside the Alamo walls, their heroism inside those walls isn’t diminished. A man can live as a son-of-a-bitch his entire life and still deserve to be honored for the heroic, good things he did.”

I apply that same logic here, to practice historical tolerance I preach. I don’t view the butcher of Texians as a hero. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna was flighty, self-serving and vain in dealing with his own people.

He freed slaves while marching through Texas as a political and military strategy, while using forced labor on his own haciendas. He did gruesome things in times of war. By all accounts, he was an SOB for 99% of his life.

But he did some lasting good for the people of Turbaco and helped them advance their pursuit of happiness. The tabaqueros were brought out of abject poverty by a man who was seemingly malevolent otherwise.

I ask y’all, in earnest – should we fault the people of Turbaco for celebrating him, even if our own view of the man is wildly different from theirs?

Categories: Texas history